Hirschler Celebrates Black History Month

This month, Hirschler joins with the Library of Congress, the National Archives and Records Administration, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Gallery of Art, the National Park Service, the Smithsonian Institution, and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, in paying tribute during Black History Month to the generations of Black Americans who struggled with adversity and prejudice to achieve full citizenship in American society. And the struggle continues.

The origin and evolution of Black History Month in the United States begins in the 1920s with Harvard-educated historian Carter G. Woodson, who held a dream that truth could not be denied and that reason would always prevail over prejudice. Woodson’s hopes to raise awareness of Black Americans' contributions to civilization and American society were realized when he and the organization that he founded, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, conceived and announced Negro History Week in 1925, an event that was first celebrated during the week in February, 1926 that encompassed the birthdays of both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. The national response was immediate and overwhelming. Black History clubs sprang up nationwide. Teachers demanded materials to instruct their students in Black American history and culture. And progressive folk of all colors stepped forward to endorse the effort.

By the time of Carter Woodson’s death in 1950, Negro History Week had become a central part of Black American life and culture, and substantial progress had been realized in bringing white Americans to a greater appreciation of the celebration. In the 1950s, mayors of cities nationwide issued proclamations noting Negro History Week. The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s dramatically expanded the consciousness of all Americans of the importance of Black history, culture, and contributions.

The celebration was expanded to the entire month of February in 1976, our nation’s bicentennial. President Ford urged all Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.” And thus, fifty years after the first Negro History Week, Carter Woodson’s Association, now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, held its first Black History Month, and every U.S. president since has issued Black History Month proclamations.

In 2022, we honored the accomplishments and contributions of four Black Americans, two women and two men, all of whom had Virginia connections: Rosa L. Dixon Bowser; William B. Robertson; Lucy Francis Simms; and Dr. Isaac David Burrell. Last year we honored Sarah Garland Boyd Jones, Virginia’s first Black woman physician, Dr. Robert Walter Johnson, mentor of tennis greats Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe, and Norvel Lee – Virginian, World War 2 Veteran, US Olympian, and civil rights warrior and pioneer. We also remembered last year the day in August, 1963, that Dr. Martin Luther King, inspired by Mahalia Jackson, made history at the Lincoln Memorial, and then gave a special gift to future basketball Hall of Fame coach George Raveling.

This year we honor American jazz musician and bandleader Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, novelist Toni Morrison, and enslaved Virginian Elizabeth Heckley, who later worked in President Lincoln’s White House and became a confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln.

2024

Honoring Virginia's Own Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly

In this last installment of our 2024 Black History Month series of profiles of significant figures from American Black History, we remember and honor native Virginian Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly, who was born into enslavement and then rose to become an integral part of President Abraham Lincoln’s White House.

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly was born in 1818 in Dinwiddie County, Virginia on the plantation property of Armistead Burwell, who is believed to have been Elizabeth’s biological father following a non-consensual encounter with Elizabeth’s mother Agnes “Aggy” Hobbs. Nonetheless, and despite her parentage, Elizabeth Hobbs was born enslaved and remained enslaved until her emancipation in 1855 at the age of 37. Elizabeth’s mother’s husband, George Hobbs, was an enslaved man who worked on a neighboring plantation and, even though Elizabeth was not his child, he was devoted to Elizabeth and her mother, and Elizabeth considered George Hobbs to be her father and loved him as such.

Elizabeth grew up with other enslaved children as well as the Burwell children (the children of her enslavers), was well-liked by all, and was even permitted by the Burwell family to learn to read and write, a somewhat unusual privilege for an enslaved child. She also learned to sew and make clothing, a skill taught to Elizabeth by her mother Aggy. But Elizabeth also learned of the cruel realities of enslavement when her father George was forced to leave Virginia, and his wife Aggy and daughter Elizabeth, when his owner/enslaver sold his plantation and left the state, taking Elizabeth’s father with him. George Hobbs was given two hours to say goodbye to his family, and Elizabeth later wrote of the heartbreak of that day. “I can remember the scene as if it were but yesterday – how my father cried out against the cruel separation, the tears and sobs – the fearful anguish of broken hearts. The last kiss, the last good-by, and my father was gone forever.” Elizabeth never saw her father again.

In 1832, when Elizabeth was fourteen years old, she was sent to North Carolina without her mother to work for the son of Elizabeth’s Virginia enslaver. In 1838, while she was still enslaved in North Carolina, Elizabeth was subjected to repeated acts of sexual violence at the hands of a local store owner, and became pregnant and gave birth to her only son and child, George, named for the man that Elizabeth considered to be her lost father, George Hobbs. Elizabeth's words about George’s birth reveal deep pain: “If my poor boy ever suffers humiliating pangs on account of birth . . . he must blame the edicts of that society which deemed it no crime to undermine the virtue of girls in my then position.”

Elizabeth’s painful time in North Carolina ended in 1842 when she returned to Virginia, and then moved in 1846 with her new owner to St. Louis, where she soon gained notoriety in local society circles as a skilled dressmaker. In 1850, Elizabeth married James Keckly, who Elizabeth believed to be a free Black man but who Elizabeth later learned was a fugitive slave. Nonetheless, Elizabeth continued building her dressmaking business and saving money in order to purchase her freedom. Finally, in 1855, Elizabeth gained her freedom in exchange for $1,200, a small fortune at the time, and received her signed emancipation papers.

Now a free woman (Elizabeth also separated from James Keckly shortly after gaining her emancipation), Elizabeth moved to Washington, D.C. in 1860, where once again she gained recognition as a dressmaker and creator of fashionable women’s clothing. One of her new patrons, Margaret McClean, commissioned a new dress from Elizabeth for a pre-inauguration dinner with the family of President-elect Lincoln at the recently opened Willard Hotel. The soon-to-be First Lady, Mary Lincoln, was so taken by Margaret McLean’s new dress that she reached out to Elizabeth and asked her to report to the White House at 8:00 a.m. on the day after the inauguration. In the spring of 1860, Elizabeth made as many as sixteen new dresses for Mary Lincoln, and the two women established a close personal as well as working relationship. When the Lincoln's son Willie died suddenly in 1862, Keckly was in the White House to grieve with President Lincoln and the First Lady. After Willie’s death, Mary Lincoln asked Elizabeth to accompany her on an extended trip to New York and Boston and, while traveling with Elizabeth, the First Lady wrote to her husband that “if it had not been for Lizzie Keckly, I do not know what I should have done.”

In addition to her dressmaking business, while in Washington, Elizabeth Keckly also found time to start a relief society known as the Contraband Relief Association to aid the “contraband” camps of enslaved war refugees that flooded into the nation’s capital. The legal status of these refugees was unclear – they were considered to be “contrabands of war” (i.e., escaped Black slaves who had found their way north), but were they enslaved or free? After establishing the Association, Elizabeth asked President and Mrs. Lincoln for a donation, which Elizabeth quickly received, and the First Family also visited the war refugees in the Washington camps.

Elizabeth Keckly worked in the White House up until President Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, less than a week after the war’s end, and then continued to work with and support Mary Lincoln in the months following President Lincoln’s death. She also continued to build her dressmaking business and later began training Black seamstresses, passing down her craft and her art. In 1892, at the age of 72, Elizabeth moved to Ohio and accepted a position as the head of HBU (Historically Black University) Wilberforce University’s Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts. After retirement from her faculty position, she returned to Washington, D.C. where she died at the age of 89 after living an extraordinary and remarkable life.

Today, Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly is one of seven remarkable Virginia women who are honored by the Virginia Women’s Monument (Voices from the Garden), just inside the Grace Street Entrance to Capitol Square in downtown Richmond. And this week, we also remember and honor Ms. Keckly, who traveled from childhood enslavement in Virginia to President Lincoln’s Civil War White House.

Honoring Toni Morrison

Novelist, playwright, editor, children’s author, essayist, college professor, lyricist, and librettist – Toni Morrison was a true giant of American letters. She stands as one of only six persons, the only Black person, and one of only two women, to have achieved the literary double knockout of the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction – the others are fellow giants Saul Bellow, Pearl Buck, John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, and William Faulkner. In awarding her the Nobel Prize in 1993, the Swedish Academy cited her body of work that is “characterized by visionary force and poetic import,” through which Ms. Morrison “gives life to an essential aspect of American reality” – the American Black experience.

Ms. Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford on February 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio, an integrated working-class community near Cleveland. Her father was a shipyard welder who insisted that young Chloe take pride in everything that she did. At 12, Chloe became a member of the Roman Catholic Church and adopted the baptismal name “Chloe Anthony,” from which her lifelong nickname of “Toni” was derived. Upon college graduation from Howard University in Washington, D.C., Toni Morrison earned a master’s degree in English from Cornell University in 1955 and then embarked on her academic career, teaching English for two years at Texas Southern University, a historically Black institution in Houston, before returning to Howard as a tenured faculty member.

In the late 1960s, Professor Morrison moved to New York City and accepted an editorial position with legendary publishing house Random House, where her authors included key Black figures Angela Davis, Gayl Jones, Toni Cade Bambara, and Muhammad Ali. By the 1970s, Ms. Morrison had turned her hand to her own writing, publishing in 1977 her first great novel “Song of Solomon,” for which Ms. Morrison received the National Book Critics Award in 1978. Ms. Morrison’s literary masterpiece “Beloved” was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1988, and in August, 2019, after polling hundreds of writers, editors, and literary critics, the New York Times Book Review named “Beloved” as the single best American work of fiction of the previous quarter-century. As explained by Ms. Morrison after the success of “Beloved,” she was working to “get down to the craft of writing, where Black people are talking to Black people.”

In addition to her Nobel and her Pulitzer and many other distinguished literary awards, Ms. Morrison received the 2000 Library of Congress Bicentennial Living Legend award, the 1994 Pearl S. Buck Award, the 1993 (Paris) Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters, the 1978 Distinguished Writer Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and, capping off a lifetime of accomplishment and achievement, Professor Morrison in 2012 received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, presented by President Barak Obama.

Toni Morrison passed away in August, 2019, but her life’s work and legacy live on. Ms. Morrison’s vision for America is perhaps nowhere more vividly illustrated than it is at the conclusion of her first great novel “Song of Solomon,” when her character Macon, known as “Milkman,” after a lengthy examination of his family’s ancestral history, finally attains the knowledge and quiet confidence that allows him to find his place within his family, his community, and within Black America. And at that moment, in the novel’s final paragraph, Milkman leaps joyously into the air, taking flight over his world. Sail on, Toni Morrison.

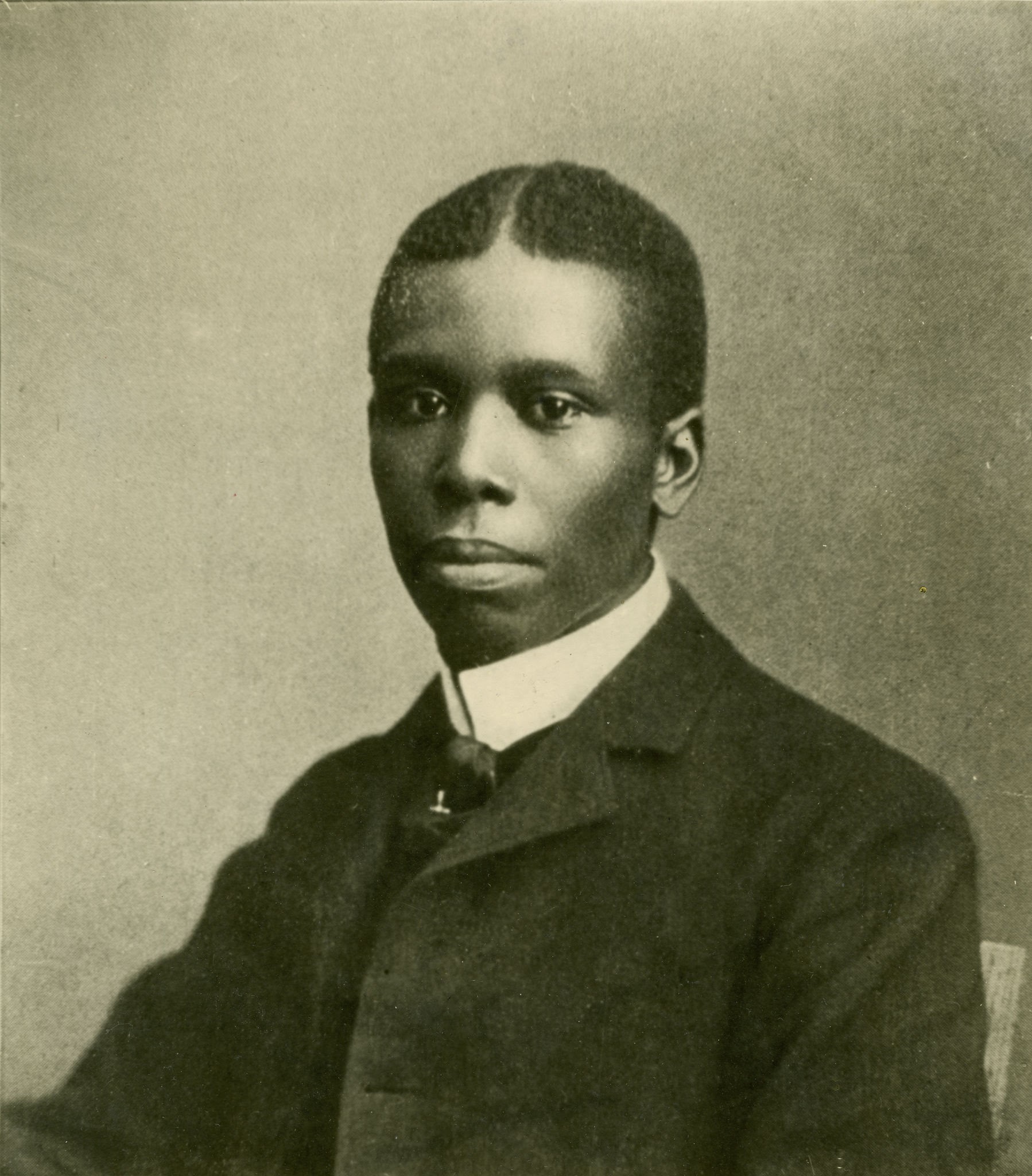

Honoring Paul Laurence Dunbar

Paul Laurence Dunbar, who became the first Black poet to be widely recognized and acclaimed in U.S. literary circles, was born in Dayton, Ohio in 1872 to formerly enslaved parents who had migrated to Ohio from Kentucky. Young Paul Dunbar began showing literary promise while still in high school in Dayton, where he was the only Black student in his class. He was president of his school’s literary society, editor-in-chief of the school paper, and was elected school “Poet Laureate.” By 1889, when Paul was only 17 years old and still in high school, the Dayton Herald (the local Dayton daily newspaper) had already published a series of Paul’s poems and he began editing the Dayton Tattler, a local Black-owned newspaper.

As recognition of his work and talent began to spread, Dunbar self-published his first volume of poetry, Oak and Ivy, in 1893. Oak and Ivy gained “word of mouth” acclaim and sold well, leading to publication of Dunbar’s second volume of verse, Majors and Minors, as well as a six-month lecture and reading tour of Great Britain. When Dunbar returned to the United States, he obtained a clerkship at the U.S. Library of Congress, where he published his first collection of short stories, Folks from Dixie, in 1898. Despite its harshly critical commentary on persistent racial prejudice and inequity in the U.S., Folks from Dixie sold well and was well-received by Dunbar’s growing audience.

Paul Laurence Dunbar died before his time, in 1906 at the age of only 33, but his work remains a legacy of the past and a beacon for the future. Today, he is recognized as the first writer of any color to articulate to a diverse audience the Black experience in America in all of its embodiments. His work set the stage for the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 30s and influenced future generations of poets, including the great Black poet Langston Hughes. And Paul Dunbar wrote more than just outstanding poetry and stories – he produced lasting literature in all venues – poetry, novels, stories, and more. He was a journalist and a Broadway lyricist, as well as an outspoken political speech-writer. But it is Paul Dunbar’s poetry for which he is best remembered today.

We honor the life, legacy, and enduring work of Paul Laurence Dunbar, and we close with Dunbar’s great poem, Ships that Pass in the Night, which was written in contemplation of the end of the insidious institution of Black enslavement in the United States. Ships that Pass in the Night has been recognized for its use of repetition and rhyme to create a strong aura of melancholy and a sense of regret and grief for a loss that cannot be reclaimed.

Ships that Pass in the Night

Out in the sky the great dark clouds are massing;

I look far out into the pregnant night,

Where I can hear a solemn booming gun

And catch the gleaming of a random light,

That tells me that the ship I seek is passing, passing.

My tearful eyes my soul’s deep hurt are glassing;

For I would hail and check that ship of ships.

I stretch my hands imploring, cry aloud,

My voice falls dead a foot from mine own lips,

And but its ghost doth reach that vessel, passing, passing.

O Earth, O Sky, O Ocean, both surpassing,

O heart of mine, O soul that dreads the dark!

Is there no hope for me? Is there no way

That I may sight and check that speeding bark

Which out of sight and sound is passing, passing?

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thank you Paul Dunbar.

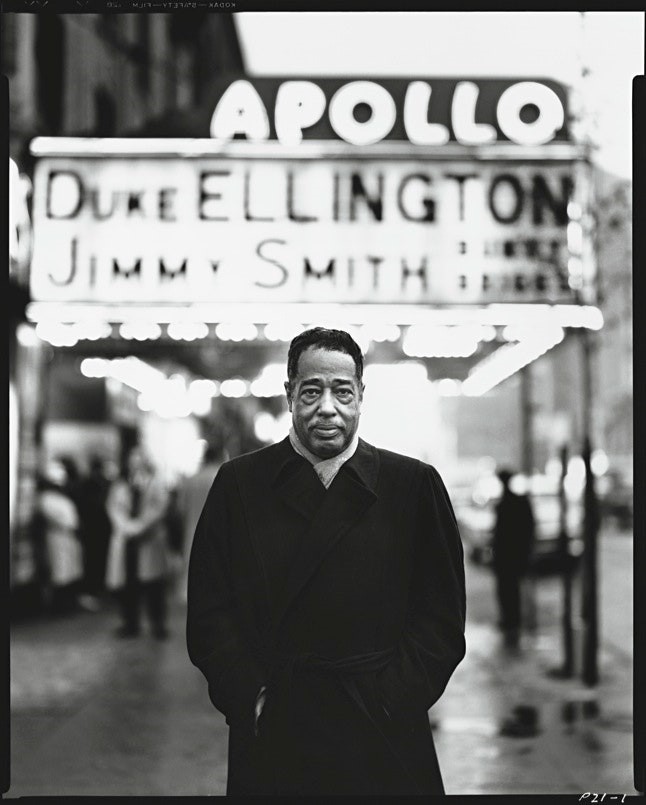

Honoring Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington

Duke Ellington’s contributions to jazz and American music are incalculable. As a bandleader, his orchestra was, along with the Count Basie Orchestra, one of the country’s two best from the 1920s until the early 1970s. As a composer, Ellington wrote literally thousands of pieces, hundreds of which have become standards of the “Great American Songbook,” including great tunes such as Mood Indigo, Solitude, In a Mellotone, Caravan, Take the A-Train, and so many more. As an arranger, Ellington was particularly innovative, charting expressly to the specific talents of his individual players and soloists, and constantly rearranging his “standards” (“Caravan” did not sound exactly the same in the 1970s as it did in the 1950s). And we sometimes forget that the Duke was a sublime musician and pianist himself, influencing the playing styles of a generation of younger pianists such as Thelonious Monk and Cecil Taylor. There is simply no logical explanation for the musical genius of Duke Ellington.

“Duke Elegant” was born Edward Kennedy Ellington in 1899 in Washington, D.C. and early on earned the nickname “Duke.” At the turn of the century, the District was more racially tolerant than many other parts of the U.S. The city boasted the largest Black urban population in the country, with 31% Black residents and segregation laws that were, relatively speaking, somewhat relaxed. The teachers at Ellington’s segregated school taught American Black history, and worked to instill a deep sense of pride in their young students, a sense of pride and identity that Duke Ellington retained and infused into his music throughout his life. As Ellington once wrote, “[t]he music of my race is something more than the American idiom. It is the result of our transplantation to American soil, and was our reaction in the plantation days to the tyranny we endured. What we could not say openly, we expressed in music.”

Ellington as a child learned piano from his mother, and moved to New York City when he was 24 years old, where he organized his first band. By 1927, Ellington’s “orchestra” had secured a permanent engagement at Harlem’s legendary Cotton Club, which gave him access to larger audiences, radio performances, and recording opportunities. By 1931, Duke Ellington and his orchestra had left the Cotton Club, embarking on a series of extended tours and engagements throughout the country. A tireless road warrior, Ellington continued to tour extensively and perform live shows for the rest of his life, winning audiences, fans and followers throughout the U.S and Europe.

Ellington did some of his best and most innovative writing while on the road, and he was a pioneer of the extended jazz “suite” format. Never was Ellington’s impact on music and culture felt more profoundly than on the night of January 23, 1943 at New York’s Carnegie Hall with the premiere of Ellington’s major jazz composition “Black, Brown and Beige: A Tone Parallel to the American Negro.” The performance that night was nothing short of revolutionary. The first section, “Black,” paid homage to enslaved Black Americans. The second section, “Brown,” follows the emancipation of enslaved Black Americans into the Jim Crow era and through two world wars, including a section which highlights the sacrifices of Black American soldiers who fought valiantly for the same nation that had enslaved Black lives. The third section, “Beige,” Ellington wrote, is about Black Americans who, despite the progress that had been made, “still do not have enough to eat or a place to sleep.” Ellington’s hope for “Black, Brown and Beige” was that it would educate and unify.

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington was awarded the President’s Gold Medal by President Johnson in 1966, the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Nixon in 1969, the French Legion of Honor (France’s highest national decoration) in 1973, and posthumously, in 1999, the Pulitzer Prize in Special Citations and Awards, for his life’s work in music and humanitarian causes. And Duke Ellington influenced and continues to influence generations of great musicians in all musical genres, including the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, Dr. John, Billy Joel, Eric Clapton, and Bob Dylan. And in 1976 none other than the great Stevie Wonder paid homage to Duke Ellington with his song “Sir Duke” on the great album “Songs in the Key of Life.”

Edward Kennedy Ellington passed away on May 24, 1974, a month after his 75th birthday, and is buried in the Bronx in New York City. An overflow crowd of over 12,000 people attended his funeral, held at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, including a roster of the most important and influential American musicians of the day. And the great Ella Fitzgerald summarized the sentiment of the occasion by saying “it’s a very sad day . . . a genius has passed!” We honor the life, legend, accomplishments, and contributions to American life and culture of Edward Kennedy Ellington.

2023

Honoring Virginian Norvel Lee

Norvel Lee was born in 1924 in the Southwest Virginia community of Lick Run, and grew up in Botetourt County, Virginia. Lee went on to become the first Black Virginian to win Olympic Gold, capturing the light heavyweight boxing gold medal at the 1952 Olympic games in Helsinki, Finland. In winning gold at the ’52 games, Lee won four straight matches by unanimous decision and was voted the most outstanding boxer in any weight class. But in 1948 (seven years before Mrs. Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama), Lee faced an even tougher opponent when he challenged, and defeated by knockout, his criminal conviction for declining to surrender his seat to a white person on a passenger train in Alleghany County, Virginia. Despite these accomplishments, generations of Virginia public school students (including this correspondent) have graduated high school in the Commonwealth without ever learning of the life, legacy, and accomplishments of Norvel Lee.

Norvel Lee grew up in Southwest Virginia with a speech impediment that not only subjected him to ridicule by his classmates but that also hampered his academic progress. Nonetheless, he graduated from Fincastle’s (segregated) Academy Hill School for Negroes in 1943 as, in the words of one of his teachers, “the most academically motivated student” in the school’s history. And in the midst of World War II, the eighteen-year old Lee enlisted in the US Army Air Corps where he became one of the famed “Tuskegee Airmen,” serving in combat in the South Pacific.

After the war, Lee matriculated at Washington, D.C.’s Howard University, where he first learned the art of the “sweet science” and participated in intramural boxing matches. Against all odds, Lee later earned a spot on the 1948 US Olympic boxing team as an alternate. He didn’t box at the 1948 games in London, but following the games he returned to Virginia to visit family in Botetourt County. And it was on that return trip home, after fighting for his country in WW2 and representing his country abroad in the Olympics, that Lee was arrested on a passenger train between Covington and Clifton Forge, Virginia for declining to surrender his seat to a white passenger and leave the “whites-only” section of railway car. True to his nature, Lee decided to fight the conviction and engaged Richmond lawyer Martin A. Martin from the famed Richmond firm of Hill, Martin & Robinson – the “Hill” being Oliver Hill of Brown v. Board of Education fame, and the “Robinson” being Spottswood W. Robinson III, for whom the federal courthouse in Richmond is now named. And in 1949, the Virginia Supreme Court agreed with Lee and Martin, holding that segregation on public vehicles in interstate transportation was unlawful. Norvel Lee’s case subsequently became a tool for other civil rights lawyers to continue making dents in the institution of segregation in other cases, including, ultimately, Brown.

Norvel Lee made it back to the 1952 Olympic games, joining another Black US boxer, Floyd Patterson, in winning gold. Unlike Floyd Patterson (who went on to have a pretty good pro career), Lee declined to turn pro following the ’52 games, returning instead to Howard in order to graduate and begin his career in Northern Virginia and Washington as an educator, real estate investor and reserve military officer, ultimately retiring from the Army Reserves as a lieutenant colonel. Norvel Lee passed away in 1992 at the young age of 68. His legacy endures, however, and his story needs to be told. Today, we honor a diverse group of accomplished Virginians with monuments on Capitol Square in Richmond, but Norvel Lee is not among this group – so far. Perhaps there is a place for Norvel Lee on Capitol Square, and surely there is a place for him in the history books of Virginia’s public schools. Norvel Lee – Virginian, World War 2 Veteran, US Olympian, and civil rights warrior and pioneer.

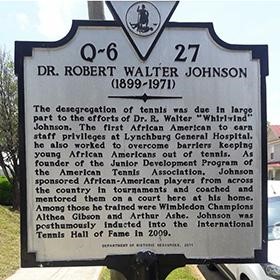

Honoring Dr. Robert Walter "Whirlwind" Johnson

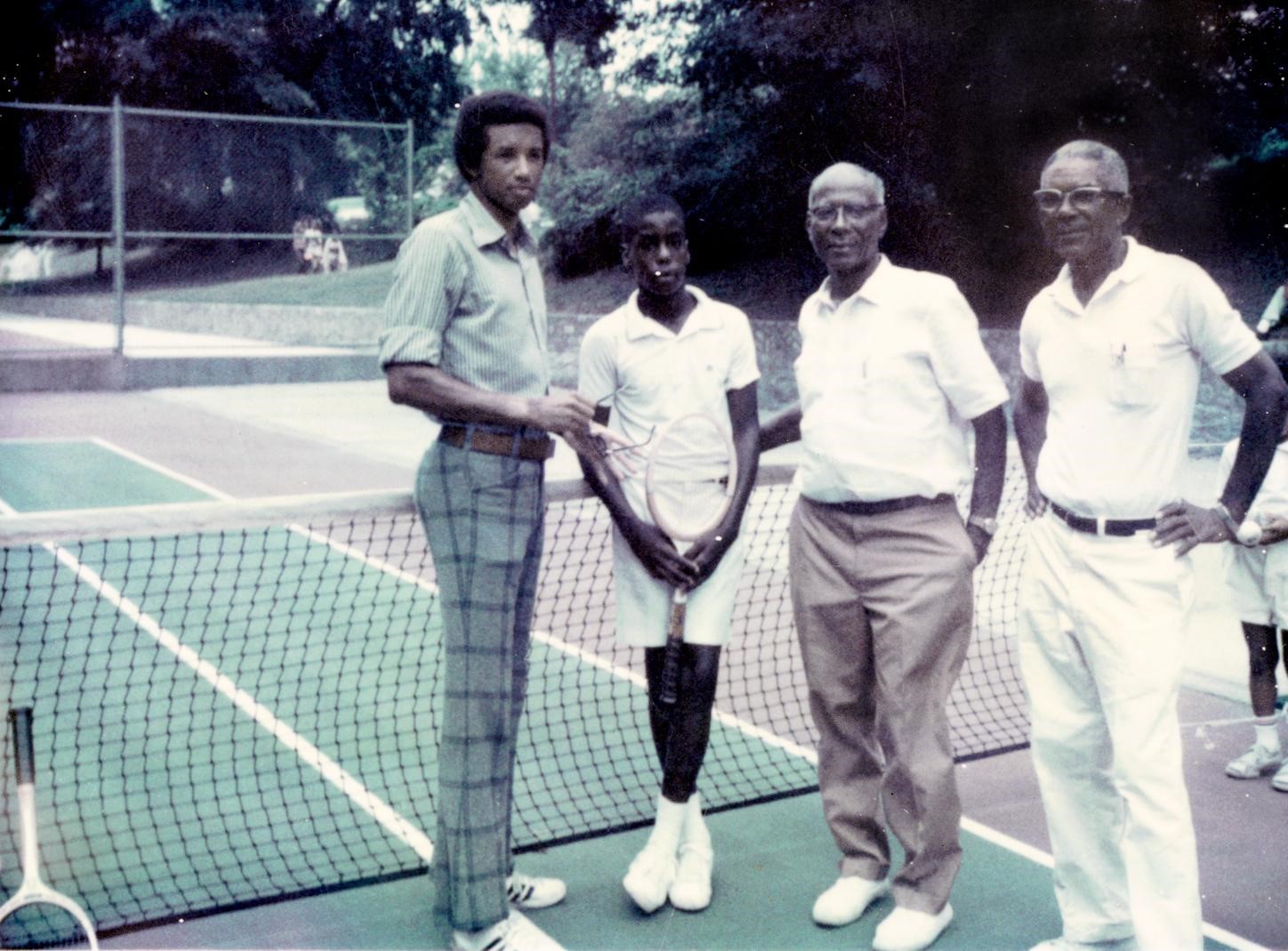

(Pictured above, Dr. Johnson, third from left, and Arthur Ashe, far left, along with two unidentified friends.)

The house situated at 1422 Pierce Street in Lynchburg, Virginia is a modest home surrounded by a modest yard in a modest Lynchburg neighborhood. A casual passerby would not look twice. But there are two things about the residence at 1422 Pierce Street that distinguish it from other houses in the neighborhood. First, there is a tennis court in the backyard. Second, situated on Pierce Street in front of the house stands one of those ubiquitous Commonwealth of Virginia Historical Markers that populate so many highways and historical sites throughout the Commonwealth. The Pierce Street marker, designated as Historical Marker Q-6-27, identifies the tennis court in the backyard of 1422 as the court that improbably produced the first Black tennis players to win singles championships at the tennis world’s four “Grand Slam” tournaments: the United States Open, Wimbledon, the French Open, and the Australian Open. And the house, now the culmination of hundreds of tennis pilgrimages every year, is identified as the residence of Dr. Robert Walter “Whirlwind” Johnson, also known as the Godfather of Black Tennis.

Robert Walter Johnson was born in Norfolk, Virginia in 1899, the first-born of a timber and lumber contractor and a homemaker and mother of five subsequent children. Robert was a gifted athlete and excelled at football from an early age, ultimately earning HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) All-American honors in football at Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University. In addition to the national recognition, and because of his frenetic style of play, he also earned the nickname “Whirlwind” in college. But Whirlwind also excelled academically at Lincoln and, after graduation, the future Dr. Johnson enrolled at HBCU Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, completing his medical studies in 1932.

Dr. Johnson returned to Virginia following medical school, establishing a private practice in Lynchburg, where with talent and a strong work ethic, he began to shatter professional and civic racial barriers. Lynchburg society, like society in the rest of Virginia in the 1930s and beyond, was completely segregated. Black and white children attended separate public schools, participating in separate and segregated athletic programs, and the Black schools always had inferior academic and athletic facilities. Churches and all public facilities, including hospitals, were segregated. But Dr. Johnson quickly distinguished himself as one of Lynchburg’s best, and most generous, physicians, and white families began calling on him as patients. A Lynchburg colleague and fellow physician remembers that Whirlwind “had quite a few white patients – they used to tell him what the white doctors were saying about him!” Dr. Johnson subsequently became the first Black doctor to be granted staff privileges at segregated Lynchburg General Hospital (Black patients were not allowed to enter the hospital through the front door, instead using a side door) and Dr. Johnson later became the first Black physician to deliver a baby at Lynchburg General.

In 1936, Dr. Johnson moved his family into the house at 1422 Pierce Street in Lynchburg, located in what was then a predominantly white neighborhood. The two-story house was situated on just enough real estate to build what Dr. Johnson now considered a necessity – a clay tennis court. Whirlwind had played tennis casually in college, but at age 37 he no longer dazzled crowds with whirlwind speed on the gridiron, and tennis had become a passion.

Dr. Johnson’s medical practice continued to thrive, as did his enthusiasm for tennis, which spilled over into a passion for creating opportunity for young Black players to refine their skills and compete with white players at youth tournaments around the Commonwealth. In 1951, Dr. Johnson started the American Tennis Association’s Junior Development Program at the court in the backyard of 1422 (founded in 1916, the ATA focuses on promoting Black tennis in the US). Each summer, a dozen or so gifted players from around the country, handpicked by Dr. Johnson, would take up residence in Lynchburg and train Monday-Thursday on the Pierce Street court. On Fridays, they would load into cars for weekend tournaments, competing against mostly white opponents. Remembers one veteran of Dr. Johnson’s summer tennis camps, “Dr. Johnson insisted that we play all close balls on our side of the net and call them “in,” even if we knew they were “out” – ‘give them to your opponent,’ he said, to make sure that there is no sense of impropriety.”

One of those summer campers was a teenager named Althea Gibson, who became the first Black player to win a Grand Slam tournament, doing so at the French Open in 1956, and again at the US Open in 1957, when she became the No. 1 ranked woman player in the world. In 1953, a nine-year old camper named Arthur Ashe arrived in Lynchburg from Richmond, where his father worked for the City of Richmond Parks Department but where young Arthur was not allowed to play on the all-white Byrd Park courts. Arthur Ashe would spend his next seven summers in Lynchburg with Dr. Johnson and went on to become the only male Black player to win Wimbledon (defeating Jimmy Connors in a memorable 1975 match), and the US and Australian Opens. Until his untimely death in 1993, Arthur Ashe always remembered Dr. Johnson as his most powerful mentor.

Dr. Johnson passed away in Lynchburg in 1971, but his legacy endures. He was inducted, posthumously, into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island in 2009. The house and court on Pierce Street still exist, but there is work to be done. In 1981, a then-young mechanical engineer and tennis enthusiast working and playing weekend tennis in Roanoke, Virginia made the pilgrimage from Roanoke to Lynchburg to see the court where Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe became great players, but was heartbroken to find the house in disrepair and the court giving way to weeds and vines. Fortunately, the United States Tennis Association restored the court in 2017, celebrating the 60th anniversary of Althea Gibson’s US Open championship. The court is now used by the Lynchburg Parks and Recreation Department for free youth tennis programming – one believes that Arthur Ashe would be proud.

“This court represents a significant part of American history and civil rights,” says Dr. Johnson’s grandson, Robert Walter Johnson III. “This is the court where the color line in tennis was changed forever.” And for that we thank you, Dr. Robert “Whirlwind” Johnson.

Honoring Sarah Garland Boyd Jones

Sarah Garland Boyd Jones, Virginia’s first Black female physician, was born in the midst of the Civil War, in Albemarle County, Virginia, in February, 1866, the daughter of a homemaker mother and a building contractor father. After the war, in the late 1860s, the family moved first to Henrico County and then to the City of Richmond, where her father became a well-known and in-demand builder who built, among other notable Richmond structures, the Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church in Jackson Ward, and the headquarters of the Grand Fountain United Order of True Reformers, an African American fraternal organization that was founded in Richmond and that became the largest and most successful Black business enterprise in the United States between 1881 and 1910.

Sallie Boyd, as Dr. Jones was known in her youth, attended the Richmond Colored Normal School, where she was a classmate of Maggie Walker, and from which Ms. Jones graduated in 1883. Upon graduation, Ms. Jones became a teacher at Richmond’s Baker School, where she remained on the faculty until 1888, when she married fellow teacher Miles B. Jones.

In 1890, Sarah Jones began her medical studies at Howard University in Washington, D.C., receiving her M.D. degree in 1893. And on April 27, 1893, Sarah G. B. Jones became the first Black woman to pass the Commonwealth of Virginia Medical Examining Board’s licensing examination, receiving the highest score of the eighty-six applicants in surgery and general practice.

Sarah Jones established a medical practice in Richmond, and offered a one-hour free clinic every day during the week for women and children who could not afford decent medical care. During the 1890s, Dr. Jones was one of only three women physicians (and the only Black female doctor) and one of only about half a dozen Black physicians in Richmond.

Because Black physicians at the time were not granted admission to the all-white medical professional societies and organizations, Dr. Jones and her husband, who had earned his M.D. from Howard in 1901, established the Medical and Chirurgical (i.e., “Surgical”) Society of Richmond (“MCSR”) in 1902. That same year, because Black patients did not enjoy admission privileges at all-white hospitals in Richmond at the time, and because sufficient numbers of decent treatment facilities for people of color were badly needed, Jones, her husband and several other members of the MCSR established the Richmond Hospital Association (“RHA”). The next year, in 1903, RHA purchased a house in what is now the Gilpin Court neighborhood, where it opened in the same year both a hospital for Black patients as well as a nursing school.

Sarah Jones continued with her own successful private practice, treating Black and white patients alike. Jones and her husband resided in Jackson Ward and were active in both the civic and the professional life of the City. In 1905, the City of Richmond, Richmond’s Black community, and the City’s medical and civic communities, endured a devastating loss when the City lost Dr. Sarah G. B. Jones to an untimely death after Dr. Jones suffered what is now believed to have been a stroke. Following a funeral attended by hundreds of Richmonders both white and Black, Sarah Jones was buried in Richmond’s historic African American Evergreen Cemetery in the City’s East End.

In 1922, the Sarah G. Jones Memorial Hospital in Richmond’s East End was named in honor of Dr. Jones. The hospital was re-named Richmond Community Hospital in 1945 and is today part of the Bon Secours network. Sarah Jones’s memory lives on, however, in the Bon Secours Sarah Garland Jones Center for Healthy Living, a place for families, civic and religious groups, non-profits, and the entire Richmond community to learn, gather and socialize. The Sarah Garland Jones Center is a site of health, hope, and well-being that sponsors a wide variety of wellness programming, including hands-on cooking classes, nutrition information and classes, group-based therapy for adolescent behavioral health, and wellness therapies for hypertension, diabetes and cardiac conditions. Thus, the legacy of Sarah Garland Boyd Jones, medical trailblazer and civil rights champion, lives on and continues to serve and inspire multiple generations of all Virginians.

Honoring George Raveling, Mahalia Jackson, and Martin Luther King

George Raveling is a Hall of Fame college basketball coach who was a trailblazer – a member of the first wave of Black basketball coaches at predominantly white colleges and universities. Raveling was a player at Villanova University during the segregated late 1950s and later coached at Washington State University (where he was the first Black head coach in what was then the Pac-Eight Conference), the University of Iowa, and the University of Southern California. But in August, 1963, Raveling was a 26-year old security guard at the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom – and on Sunday, August 28, 1963, Raveling was standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, just a few feet away from Dr. Martin Luther King as Dr. King delivered his historic “I Have a Dream Speech.” And, improbably, George Raveling left the Lincoln Memorial that day with the original typed manuscript of Dr. King’s speech – the very manuscript used by Dr. King – in his pocket!

Raveling recalls that when Dr. King began speaking that day, he spoke mostly with his eyes fixed on the script before him, and Dr. King appeared to be slightly nervous. Dr. King began the speech reading the words “five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice . . . .”

As Dr. King neared the end of his prepared remarks, he seemed to sense that his words and message were not rising to the grand spirit of the occasion. As George Raveling recalls, “I heard a powerful voice from behind Dr. King say ‘tell them about the dream, Martin, tell them about the dream!’ and that was the great gospel singer Mahalia Jackson,” who was also on the stage that day and who had performed earlier that Sunday afternoon. Raveling remembers, “Ms. Jackson had been at a lot of Dr. King’s speeches and demonstrations that summer, and she had heard Dr. King speak powerfully of his dream.” And at that point, Dr. King went “off-script” and began to riff improvisatorially on the concept of “the dream,” as Raveling would discover later that day when he read the hard copy of the speech. Dr. King began, “I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

The spontaneous, off-script crescendo to Dr. King’s speech lasted a mere two minutes and forty seconds, and consisted of only 301 words. But they were the most moving and compelling words of the day, and are three hundred of the most historic words in American civil rights history. “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed . . . that all men are created equal . . . that all people will be able to join hands and sing in the words of that old Negro spiritual – free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

As 200,000 people on the Washington Mall roared their approval, Dr. King collected his papers, turned to his left and found himself face-to-face with a part-time security guard and volunteer assistant basketball coach – George Raveling. “Dr. King,” Raveling said, pointing to Dr. King’s three sheets of typed papers, “can I have that?” King handed the three sheets of paper to Raveling, and seconds later there was a swarm of people between the two men. Raveling folded the papers and put them in his pocket. When Raveling read the typed version of the speech later that day, he discovered that there was no mention of the “dream.” Dr. King, inspired by Mahalia Jackson, had spontaneously improvised the entire conclusion.

George Raveling had those three historic sheets of paper for nearly twenty years before anyone knew that he had the original copy of Dr. King’s speech. It did not come to light until 1983 when Raveling was named head basketball coach at the University of Iowa, becoming the Big Ten Conference’s first Black head basketball coach. Today, the speech resides at Villanova University, George Raveling’s alma mater. And 85-year old George Raveling, who still sees inequity all around him, keeps marching and mentoring. After all, as he says, a person never knows when they might be in the right place at the right time.

2022

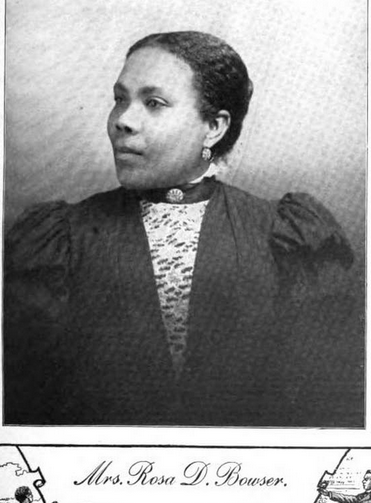

Honoring Rosa L. Dixon Bowser

Rosa L. Dixon Bowser, Virginia educator and civic leader, was born in Amelia County, Virginia on January 7, 1855, most likely into enslavement. With the end of the Civil War and the enactment of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Rosa’s family moved to Richmond to start a new life beyond enslavement, and religious faith, and education, became the family’s two pillars of strength.

Rosa was enrolled in Richmond’s public, albeit racially segregated, schools, where she promptly showed exceptional aptitude for English, mathematics, music, and language. Rosa graduated high school in 1873 as salutatorian of her class (the valedictorian was Rosa’s future husband James Herndon Bowser). Determined to have a career in education, Rosa remained at school for an additional, post-graduate year in advanced studies in Greek, Latin, music, and teaching strategies. In 1872, while still in school, Rosa successfully completed the Virginia examination for teacher certification and began her teaching career in Richmond in 1874. In 1880, Rosa and her husband James welcomed their first and only child into the world – Oswald Barrington Herndon Bowser, who later became a successful Richmond physician.

For a time after the birth of her son, Rosa taught music in her Richmond home while continuing to teach Sunday School at her church, Richmond’s largest congregation of any color, the First African Baptist Church. Rosa regarded the Richmond community as her extended family, however, and in 1883 Rosa returned to public school teaching, becoming a primary grade teacher at the Black Navy Hill School. Ms. Bowser was also deeply concerned about the continuing education of her colleagues, and began organizing “reading circles” throughout the state, groups designed to give Black teachers a forum for sharing information about courses of study, and student and teaching strategies. The success of these “reading groups” led to the formation in 1887 of the Virginia Teachers’ Reading Circle, the initial Black professional educational association in Virginia, and Ms. Bowser was president of the organization (later renamed the Virginia State Teachers Association) from 1890 to 1892.

Ms. Bowser as well as her contemporary Maggie L. Walker was also a committed proponent of universal women’s suffrage and, after the ratification in August 1920 of the Nineteenth Amendment, Ms. Bowser became the first woman in Virginia to register to vote, on September 2, 1920.

In her later years, Ms. Bowser did not slow down, continuing to teach in the (segregated) Richmond public schools until her retirement in 1923, at the age of 67. She taught Sunday School in Richmond at the First African Baptist Church for more than fifty years, until failing health forced her to relinquish that part of her life’s work. In recognition of her many contributions to education, the first branch of any Richmond public library to be open to Black patrons was named for Ms. Bowser in 1925. Ms. Bowser passed away at home in Richmond on February 7, 1931, at the age of 76.

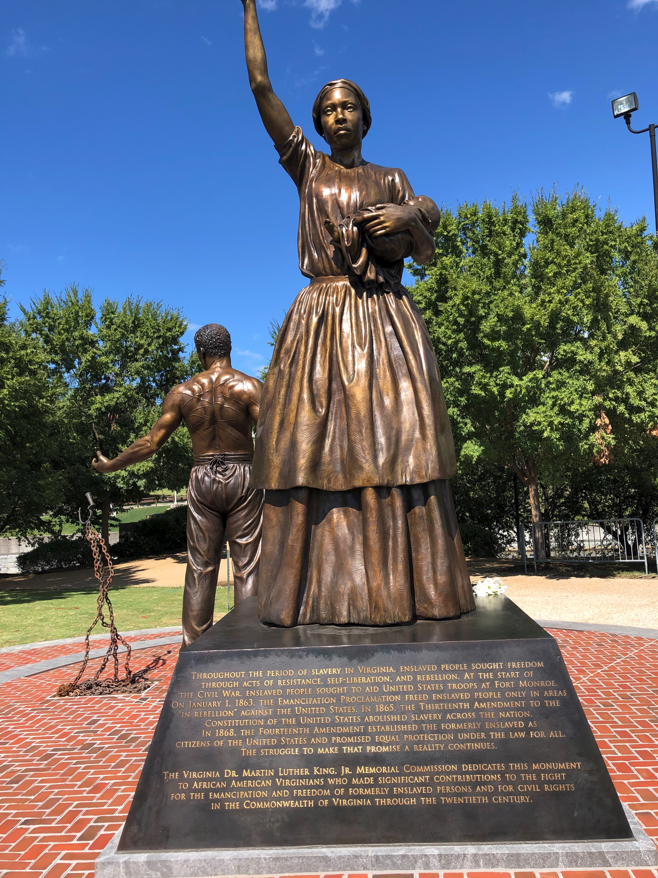

Ninety years after Ms. Bowser’s passing, on September 22, 2021, the City of Richmond dedicated the new Emancipation and Freedom Monument on Brown’s Island. The monument consists of two bronze statues dedicated to the long Black American quest for freedom and equality: a woman facing the James River holding an infant and a piece of paper bearing the date January 1, 1863, the day upon which Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation; and a man with broken enslavement shackles facing the City of Richmond. At the base of the monument, ten distinguished Black Virginians are recognized. Among the ten names at the base of Richmond Emancipation and Freedom Monument is the name of Rosa L. Dixon Bowser, whose faith and commitment to education, for all Virginians, remains an inspiration.

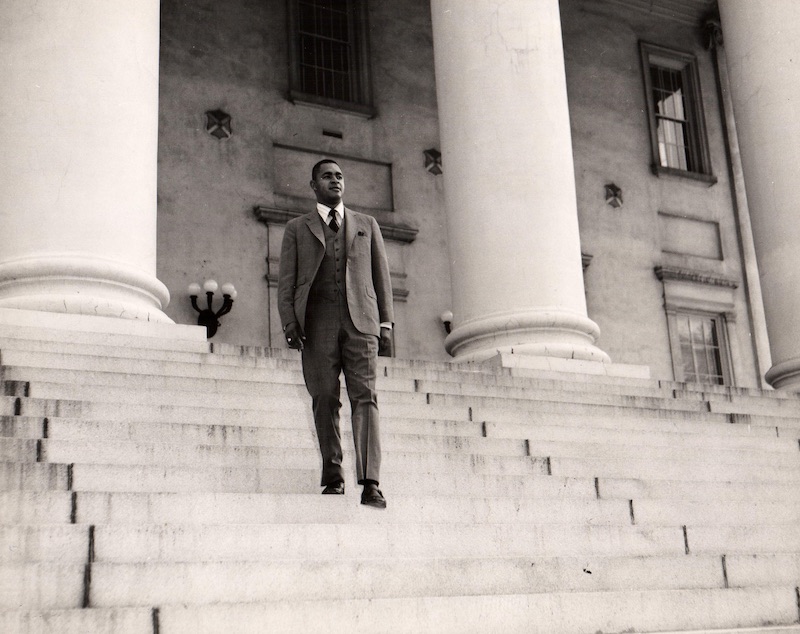

Honoring William B. Robertson

In September, 1968, Roanoke lawyer Linwood Holton had a problem. He was a Republican who wanted to be elected the following year as governor of Virginia, a state that had not had a Republican governor since 1886. Holton had another problem as well, a challenge really – he wanted to take down the segregationist “Byrd Machine” that had dominated Virginia politics and society for decades. Holton phoned his Roanoke friend William “Bill” Robertson, who was principal of Roanoke’s Hurt Park Elementary School at the time, told Robertson of his plans to run for governor, and asked Robertson to run for Virginia’s House of Delegates. Robertson replied that there were just two problems – one, Robertson was a Democrat, and two, he was Black. Holton asked Robertson to think about it, that Holton was looking to usher in a new era in Virginia politics, and wanted a diverse array of General Assembly candidates the following year when he ran for governor.

Robertson did think about it, waited until after the 1968 presidential election, switched parties and ran for a Virginia House of Delegates seat in November, 1969. Robertson lost, but Linwood Holton won, becoming the first Republican governor of Virginia in 84 years, and declared in his inaugural address that “the era of [race-based] defiance is behind us.” And three days after being elected governor, Holton again called up his friend Bill Robertson and asked Robertson to serve as a senior-level aid and decision-maker on Holton’s staff as Executive Assistant to the Governor. Robertson accepted, and his appointment marked the first time that a Black Virginian was asked to serve in the Virginia governor’s office and also made national headlines in the New York Times on January 14, 1970 (“A Negro in Virginia is Named to Staff of Governor-Elect”).

William B. Robertson was born in Roanoke in 1933 and graduated from Roanoke’s segregated Lucy Addison High School in 1950. That fall Robertson, with no money in his pocket, took a train to Bluefield State College in West Virginia where he found a job and worked out a tuition payment plan with the college president. Robertson went on to earn two Bachelor of Science degrees in education from Bluefield State and a master’s degree in education from Radford University. He later taught and coached at his alma mater, Lucy Addison H.S., before becoming principal at Hurt Park School in Roanoke and then senior aid to Governor Holton.

After Robertson’s service on Capitol Square in Richmond, he went on to serve five U.S. presidents of both parties, first with the Peace Corps under Presidents Ford and Carter, as deputy assistant secretary of state for African affairs under President Reagan, and as co-chair of a domestic task force under the first President Bush.

After his retirement from public service, Mr. Robertson did not slow down, focusing his energy in his 80s on the Black Lives Matter movement because as he said, “there is still so far to go.” Mr. Robertson passed away last June at his home in Baltimore. His memoir of his life and times in Virginia and national politics, “Lifting Every Voice: My Journey from Segregated Roanoke to the Corridors of Power,” will be published this month by the University of Virginia Press. From a 17-year old kid on a train to Bluefield, West Virginia with no money in his pocket, to Capitol Square in Richmond, to the White House, William “Bill” Robertson’s life, journey, and accomplishments remain an inspiration for all Virginians.

Honoring Lucy Frances Simms

This week we move from Roanoke and Richmond to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to learn of and honor the life of legendary and beloved Harrisonburg educator Lucy Frances Simms.

Ms. Simms, was born into enslavement by the Gray family of Virginia, who had purchased and enslaved Ms. Simms’ grandmother from a nearby enslaving Valley family years before Ms. Simms was born. Ms. Simms was seven years old and living in Harrisonburg on January 1, 1863 when President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. As a teenager, Ms. Simms later left the Valley temporarily in order to attend the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (which later became the historically Black college (“HBC”) Hampton University), graduating in 1877 at the age of twenty-one.

Ms. Simms returned to the Valley following college graduation, and began her 56-year teaching career at the Athens Colored School in the Black community of Zenda, Virginia, near Harrisonburg. Shortly thereafter, Ms. Simms moved to Harrisonburg proper, where there was not a formal school for Black children, and so Ms. Simms began teaching children in the basement of the Harrisonburg Roman Catholic Church. By 1881, the explosion in the number of her students led to the construction of Harrisonburg’s first Black school, the Effinger Street School, where Ms. Simms taught alongside her half-brother, Ulysses Grant Wilson, for the next 52 years.

Ms. Simms was more than a teacher to her students, many of whom came from homes where both parents worked multiple jobs. So Ms. Simms often helped her students to get ready for the school day, helping them dress, wash and brush and comb their hair, and sometimes feeding them breakfast. She was also a professional and community organizer and activist, helping to organize the Virginia Colored Teachers’ Association and serving as its president in 1914, and taught Sunday School and was a choir member at Harrisonburg’s John Wesley AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church. Ms. Simms also had a sense of humor. A lifelong advocate for fair pay for teachers, she once quipped, “when I calculate the time I have been teaching by years, it seems quite a while, but, when I calculate by dollars and cents, it seems but a short while!”

Lucy Frances Simms passed away at her home on East Johnson Street in Harrisonburg in 1934, at the age of 78. Her funeral, the most highly and widely attended Black funeral in the history of Harrisonburg, was attended by current and three generations of former students, fellow educators from across the Commonwealth, as well as Harrisonburg neighbors both white and Black, all of whom came to pay their respects to their beloved “Miss Simms.” And 78 years after Ms. Simms’ passing, on September 22, 2021, the City of Richmond dedicated the new Emancipation and Freedom Monument on Brown’s Island. The monument consists of two bronze statues dedicated to the long Black American quest for freedom and equality: a woman facing the James River holding an infant and a piece of paper bearing the date January 1, 1863, the day upon which Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation; and a man with broken enslavement shackles facing the City of Richmond. At the base of the monument, ten distinguished Black Virginians are recognized. Among the ten names at the base of Richmond Emancipation and Freedom Monument, and alongside the name of her contemporary and fellow educator Rosa Bowser, is the name of Lucy Simms, a child of enslavement who became a beloved Harrisonburg teacher and mentor to three generations, and a Virginia legend whose commitment to equitable pay for all teachers and to world-class education for all Virginians remains an inspiration.

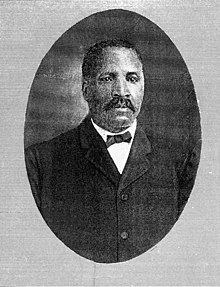

Honoring Isaac David Burrell

In the historically Black neighborhood known as Gainsboro in Roanoke, Virginia, the Burrell Center for Behavioral Health offers a broad array of medical treatment interventions for Southwest Virginians with behavioral health, developmental disability, and substance abuse issues. Too few Roanokers, however, and too few Virginians know of the rich medical legacy of today’s Burrell Center, its predecessor, Burrell Memorial Hospital, or of the compelling story of the pioneering Black physician for whom these institutions were named, Dr. Isaac David Burrell.

Isaac David Burrell was born in Amelia County, Virginia at the close of the Civil War, on March 10, 1865. Dr. Burrell’s father, Robert Burrell, was a farmer who had been enslaved before President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Young Isaac Burrell attended segregated public schools in Amelia County and then went on to graduate from Lincoln University in Chester County, Pennsylvania, the nation’s first degree-granting Historically Black College and University (HBCU). Dr. Burrell then earned his medical degree from the Leonard Medical College of Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina and received his M.D. certification in 1893.

Having completed his educational and Medical Board requirements, Dr. Burrell moved to the young industrial and railroad town of Roanoke and opened a medical practice as well as a pharmacy – the only Black-owned pharmacy in Southwest Virginia at the time. Dr. Burrell’s medical practice and pharmacy business flourished, and he became a leader in Roanoke’s Black cultural and religious life, as well as Roanoke’s business and professional communities.

In early 20th century Virginia, Black citizens in need of medical and surgical care were denied admission to “white” hospitals, solely because of their race. In Roanoke, there was not a hospital serving Black Virginians, and Dr. Burrell and several colleagues and fellow members of the Magic City Medical Society, the local organization of Black physicians for which Dr. Burrell served as president, were working to build their own hospital to serve the Black community.

The need for such an institution came into grim focus on a cold, blustery winter’s night in 1914 when Dr. Burrell, then just 48 years old, self-diagnosed the early symptoms of cholelithiasis, otherwise known as gallstones. In great pain and in acute need of surgery, Dr. Burrell drove himself to Roanoke’s Memorial Hospital, now part of the Carillion health care system, in the hope that his status as a fellow physician might cause his white colleagues to make an exception to the standing policy of refusal to admit Black persons.

Dr. Burrell shivered in the cold outside of the hospital as he waited in vain for an answer to his request for admission. Instead, he was taken to Roanoke’s train station where his colleagues placed him on a cot in a boxcar for the 250-mile trip to Howard University’s Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. When Dr. Burrell finally arrived in Washington he was suffering from jaundice, high fever, delirium, hypertension, and acute abdominal pain. He was rushed to surgery but it was too little, too late, and Dr. Isaac David Burrell died that night as a result of multiple system organ failures and sepsis. Timely surgery would certainly have saved Dr. Burrell’s life.

Back in Roanoke, and inspired and motivated by the heartbreak of the loss of their colleague, Dr. Burrell’s partners mobilized to accelerate the effort to build a Black hospital in Roanoke, and in 1915 the Burrell Memorial Hospital opened its doors to provide surgical facilities and medical treatment for the Black population of Roanoke and Southwest Virginia. Burrell Memorial was also a teaching institution and in 1925 gained state accreditation as a nursing school. In 1935, Burrell Memorial became the first Black hospital in Virginia to gain accreditation from the American College of Surgeons, and one of only 23 Black hospitals in the United States to have received ACS accreditation.

In 1955, Burrell Memorial used funding from the federal Hospital Survey and Construction Act to build the state-of-art facility in Gainsboro that today houses the Burrell Center. When President Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1965, Roanoke’s formerly white-only hospitals began admitting Black patients, and Burrell Memorial also became fully-integrated, and continued serving the Roanoke Valley until it closed as a teaching and treating hospital in 1978. The Gainsboro Burrell Memorial building later became a nursing facility until it became today’s Burrell Center in 1993.

At the beginning of 2022, as all Americans celebrate Black History Month and honor trailblazers like Dr. Burrell, we are not yet where we want to be. Too many present-day Americans of every color do not have ready access to decent health care. But because of the character, compassion, and commitment of medical pioneers and civil rights leaders like Dr. Isaac David Burrell, we are not where we were in 1914 – when a Black physician was denied admission to a “white” hospital and forced to ride over 200 miles on a metal cot in a railroad boxcar simply in order to receive decent medical care. Thank you Isaac David Burrell – we honor your life and your legacy.

2021

Honoring Shirley Chisholm

In our first week, we take a look at the life and times of Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman to serve in the United States Congress.

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1924 to immigrant parents of Guyanese and Bajan descent. Her father worked in a factory that made burlap bags and her mother worked as a seamstress and domestic worker. Ms. Chisholm graduated from Brooklyn College in 1946 and later earned a master’s degree from Columbia University while teaching nursery school and directing day-care centers in New York City. She entered the world of politics in 1964, earning a seat in the New York State Assembly, where she served until 1968.

In 1968, Shirley Chisholm made history when she became the first African American woman ever to be elected to the United States Congress, taking her seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1969, where she became a fierce advocate for the rights of the individual citizens of her inner-city Brooklyn District. Ms. Chisholm again made history in 1972, when she became the first woman, and first African American, to be widely considered a serious candidate for a major-party nomination for President of the United States. Although ultimately she did not win the Democratic party’s nomination for president, Ms. Chisholm inspired a generation of young Americans -- Black, White, women and men -- and continued to work to reform U.S. political parties to better meet the needs of everyday Americans.

Ms. Chisholm continued to serve in the U.S. House until 1983, and she passed away in 2005. This week, we honor the life, achievements, and memory of Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm, a great pioneer and champion of African American and women’s rights. For further reading on the life and accomplishments of Shirley Chisholm, click here.

Honoring Oliver Hill

In this second week of Black History Month, we remember legal and civil rights icon, and Richmond’s own, Oliver Hill.

Oliver White Hill was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1907. The family later moved to Roanoke and, in 1923 when Oliver was sixteen, to Washington D.C. so that Oliver could attend Dunbar High School, an academically elite African American college preparatory school. Mr. Hill subsequently matriculated at Howard University, working his way through college during the depths of the Great Depression, graduating from Howard in 1931, and from Howard University Law School in 1933, where he was second in his class, ranking behind only his good friend and future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. The beginning of Mr. Hill’s legal career was interrupted by World War II, during which time Mr. Hill served our country and achieved the rank of Staff Sergeant in the United States Army.

Returning to Richmond after the war, Mr. Hill resumed his law practice, partnering with fellow civil rights lawyer Spottswood W. Robinson, III. In April, 1951, Hill and Robinson took notice of a student strike at all-Black R.R. Moton High School in Farmville, Virginia, led by a young Black student named Barbara Johns, who had organized a student protest against the leaking, poorly heated buildings that served as the “separate but equal” African American high school in Farmville. Hill and Robinson later led the charge against Prince Edward County’s segregated schools in the case that defined civil rights and equal education for African American students in Virginia -- Davis v. School Board of Prince Edward County. Davis was later consolidated with four other cases in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education, in which Hill, Robinson, and Thurgood Marshall led a legal team that overturned the shameful doctrine of “separate but equal.”

Mr. Hill continued his entire life to tirelessly fight for justice, equal opportunity and civil rights, serving on Richmond’s City Council, the first African American to do so since Reconstruction. Mr. Hill also helped win landmark legal decisions involving equality in pay for Black teachers, equal access to school buses, voting rights, equitable jury selection and employment protection, served as Federal Housing Commissioner in the Department of Housing and Urban Development and, in 1993, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, by President Clinton. Today, the Richmond City Juvenile and Domestic Relations Courthouse bears Mr. Hill’s name. Mr. Hill passed away at the age of 100 in 2007, at which time his body rested in state in the Virginia Capitol.

Oliver White Hill was a legal giant and a civil rights icon, and this week we remember his life and honor his memory. Read more about the life and monumental accomplishments of Oliver Hill at the web site of The Oliver White Hill Foundation, by clicking here.

Honoring Thurgood Marshall

In the third week of Black History Month, we remember the life and accomplishments of Thurgood Marshall, the first African American justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Thurgood Marshall was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1908, descended from enslaved peoples on both sides of his family. His father, William Canfield Marshall, worked as a railroad porter. His mother, Norma Arica Williams, was a school teacher. Mr. Marshall’s parents instilled in him a love of education and the rule of law. He graduated from Lincoln University and the Howard University Law School, where he finished first in his class.

Mr. Marshall began practicing law in 1933. In 1938, he became chief counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a position in which he served until 1950. In 1953, Mr. Marshall joined a legal team that included Virginia’s own Oliver Hill and Spottswood Robinson in arguing, and winning, the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education, in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

In 1961, President Kennedy appointed Mr. Marshall to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, where he was confirmed only after overcoming opposition from a group of southern senators. And in 1967, President Johnson named Mr. Marshall to be associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, where Mr. Marshall was confirmed by a vote of 69-11, with a remarkable twenty (20) senators declining to vote either yes or no, instead choosing to vote “present” or “in abstentia.”

As an associate justice, Mr. Marshall took leading progressive positions on a broad array of issues, including affirmative action, school desegregation, the rights of welfare recipients, free speech, and capital punishment. Mr. Marshall retired from the Court in 1991, and passed away in 1993. And on January 20, 2021, Senator Kamala Harris put her left hand on a bible owned by one of her heroes, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court Thurgood Marshall, and was sworn in as Vice President of the United States -- the first woman, and the first person of color, to hold that office.”

Thurgood Marshall was a pioneer, a legal giant, and a change-making civil rights leader for all Americans. We remember his remarkable life, and honor his memory.

Honoring Barbara Johns

As Black History Month 2021 comes to a close, we honor a Virginian who as a sixteen-year-old high school student started a movement that changed public education forever in Virginia and the United States, and that led to perhaps the most famous and most important U.S. Supreme Court case in history – Brown v. Board of Education. This week, we remember Barbara Johns of Prince Edward County, Virginia.

Barbara Rose Johns was born in New York City in 1935. The family had Virginia roots and during World War II Barbara and her family moved to Prince Edward County where Barbara’s father managed the family farm while Barbara’s mother held down a job with the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C. Barbara worked on the farm and went to school. Barbara’s uncle, the Montgomery, Alabama minister and civil rights leader Vernon Johns, instilled in Barbara and her sister and brothers a passion for civil rights, education, and Black History.

Prior to Brown, Virginia’s public schools were racially segregated by state law. It was, quite literally, unlawful for Black children and White children to sit together in the same Virginia public school classroom. Racial segregation had been declared constitutional under the U.S. Constitution in 1896, in the wrongly-decided Plessy v. Ferguson. And, adding insult on top of horribly bad law, Plessy’s “separate but equal” doctrine was given little more than lip service in many counties throughout Virginia and the rest of the United States. The Prince Edward County African-American High School where Barbara Johns was enrolled, the Robert Russa Moton H.S. in Farmville, featured inadequate heating, leaking roofs, no science laboratories, and no gymnasium.

In April, 1951, sixteen-year-old Barbara Johns was working on a plan to change conditions at her school, and on April 23 Barbara delivered an inspirational speech to all 450 Moton High School students, and then led her classmates and the other students in a strike against the unacceptable “separate but equal” conditions and a march to the office of Prince Edward County School Superintendent T.J. McIlwaine, who told the students that they were “out of place.” But Barbara, who later said that “it seemed like reaching for the moon,” and the other African-American students persisted and, two days later, Barbara Rose Johns came to the attention of Richmond lawyers Spottswood W. Robinson and Oliver Hill, who subsequently agreed to take on Barbara’s cause in the case Davis v. School Board of Prince Edward County. Unsurprisingly, the Virginia state trial court in Farmville upheld the legality of the separate but completely unequal conditions but Barbara Johns, Spottswood Robinson, and Oliver Hill persisted still, joining forces with NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall to appeal Davis and a group of other “separate but unequal” cases to the United States Supreme Court, where Plessy v. Ferguson was at long last rightfully reversed in the landmark Brown case.

Following the April, 1951 march and strike, Barbara and her family were harassed mercilessly. Fearing for Barbara’s safety, her parents sent her to live with her Uncle Vernon in Montgomery. Barbara finished high school in Alabama and then attended and graduated from Drexel University in Philadelphia. Barbara’s love of learning and public education led her to a career as a school librarian in the Philadelphia public school system. She also married William Powell and together they reared five children. Barbara continued to live a quiet and productive life in Philadelphia until her untimely death from cancer in 1991 at the age of 56.

Today, Richmond’s federal courthouse on Broad Street bears the name of Spottswood W. Robinson. The Juvenile and Domestic Relations Courts Building in Richmond is named for Oliver Hill. In Washington, D.C., a statue of 16-year-old African-American student activist Barbara Johns will replace Virginia’s statue of Robert E. Lee in the National Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol. In Richmond, the Office of the Virginia Attorney General is housed in the newly-renovated and newly-renamed Barbara Johns Building. And the Virginia Civil Rights Memorial on Capitol Square in Richmond honors Barbara Johns, whose teenage likeness along with the likenesses of Barbara’s fellow Moton high School students is featured below the words, “it seemed like reaching for the moon.” This week, we gratefully honor the memory and life of Barbara Rose Johns Powell, who reached for the moon, and gained the stars.

Hirschler believes that clients are best served by a diverse group of lawyers. Learn more about our Diversity and Inclusion practices here.